Beginning March 19, 1964 at the Convair facilities in San Diego some thirty engineers and production workers dropped out of sight and were not seen on the job again for six months. Eventually approximately 200 Convair people “disappeared.” What happened to these people? Where did they go? What were they doing?

This is the story of a gamble by Convair corporate directors as American involvement in Vietnam began in early 1960. The United States did not have aircraft suited to this type of jungle fighting: a Forward Air Control (FAC) aircraft was needed. On 28 October 1964 the Navy issued a Request For Proposal (RFP) #0083-64 for a new type of plane called a Counter Insurgency (COIN) aircraft. Convair anticipated this request and thought if they could secretly and rapidly build such a plane and present a finished model ready to fly when the bidding opened, they would automatically get the contract.

Before going to Convair in February, 1964 I was working at Ryan Aeronautical in San Diego where I was the assistant foreman responsible for the electrical and instrumentation systems on their experimental vertical takeoff & landing (VTOL) aircraft, the XV-5A, so I had experience with this type of aircraft.

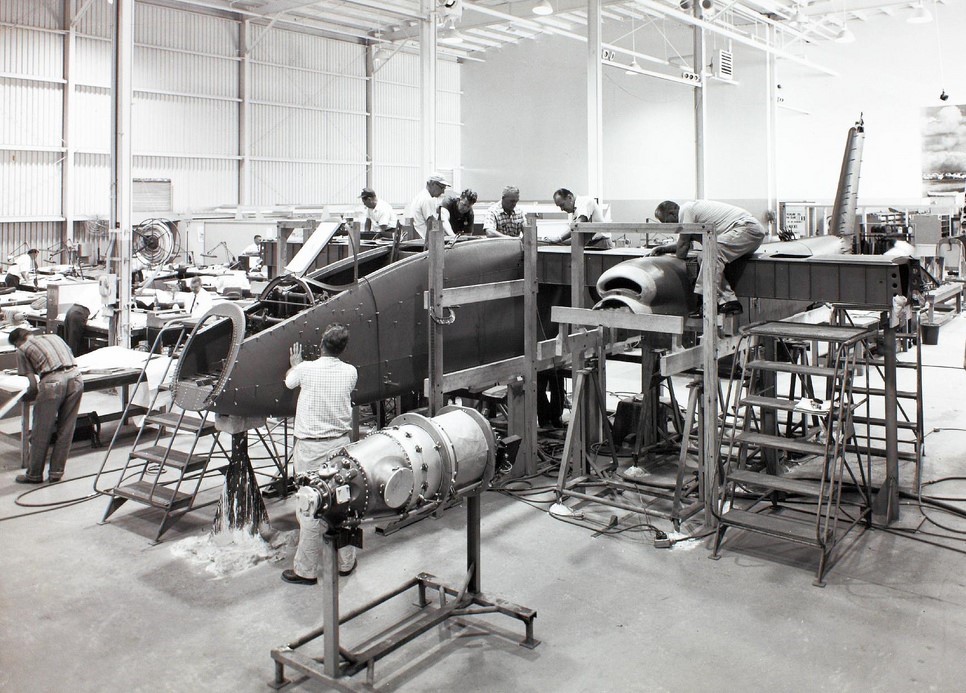

On March 19, 1964 a hush-hush Convair project to design and build the Counter Insurgency aircraft started in building 69, a locked and guarded hangar. To gain access one had to have a special magnetic card and be scrutinized by a security guard. Leaving you even had to open up your lunch box to show you weren’t sneaking anything out. None of the workers could tell what it was they were working on. In this one building the entire team of engineers, draftsmen and fabricators worked together, hand waving needed design changes.

Nick Keough, the general manager had been told about my having been an assistant foreman on the XV-5A at Ryan. He asked me to come work for him. I would have to agree to do so without even knowing what they were building and then when I went through the door, I couldn’t change my mind. He said he needed me very badly, so I agreed.

Inside the building was the framework of the new aircraft, but the project was in deep trouble. Convair, in laying off hundreds of people by seniority the previous couple years, was left with only older men that had been foremen, superintendents and managers. They had all, years ago, forgotten their working skills. Actually, by 1963, Convair was out of the airplane manufacturing business. Even the general foreman on this project had never before worked on aircraft, only production lines.

The plane was far behind schedule and work was coming to a standstill because they were ready for the wiring, instruments, instrumentation and electronic components but the assemblers working on these systems didn’t know what to do and they had no one to direct them. Keough asked me if I could help. I told him to provide me with all the electrical blueprints and a part’s list and let me alone for three days, to which he agreed. After the three days I told him how many men I needed and to give us one week and we would have the plane ready to continue construction. In doing so I worked directly with the engineer in charge of instrumentation and the electrical engineer.

As a reward for getting them back on schedule, Keough gave me an on-the-spot promotion to labor grade 1, the highest company hourly paid labor grade, ignoring the time-in-grade requirement. He called me into his office one day and told me he wanted me to be a foreman if the aircraft went into production, but it was not to be, as you will find out later!

Every Monday morning at 0800 hours, a short, to the point, no rambling meeting to iron out problems, conflicts, parts shortages, etc., was held. Each of us lead men were queried and gave a brief rundown of our progress. In just six months of two shifts a day a fully completed, ready for production aircraft was rolled out. For the roll out ceremony, they had coins (get the connection – COIN) printed up that said, “A Bird in Hand is Worth Two in the Bush.”

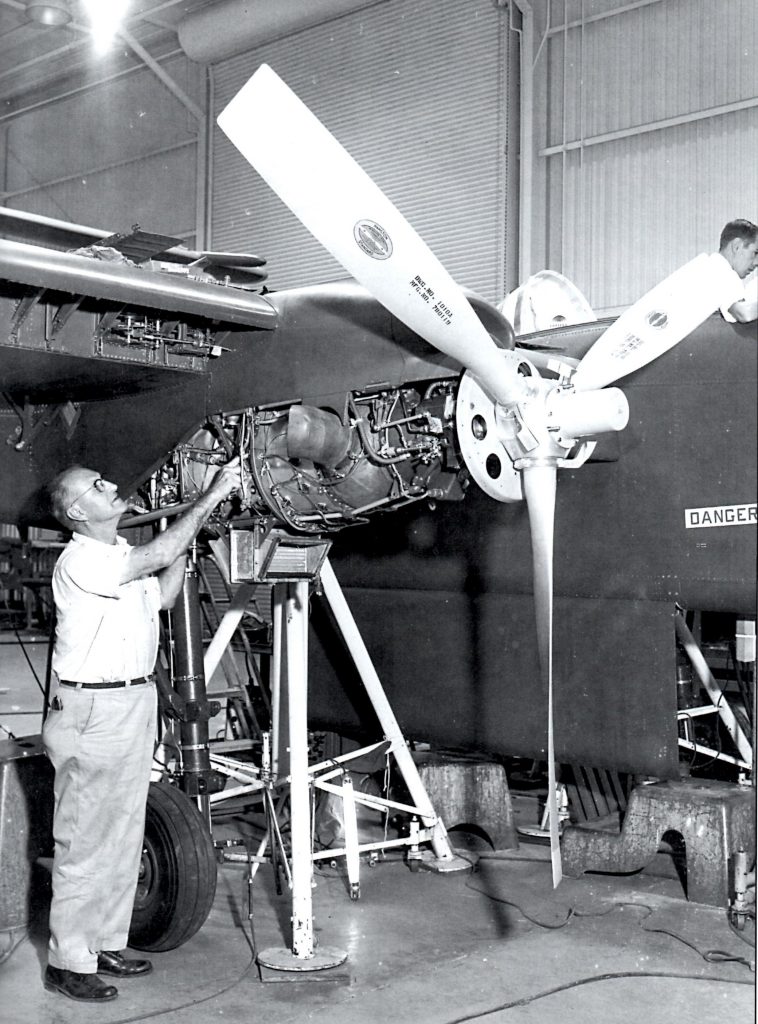

Enough parts for two aircraft were fabricated but only one plane, designated the Model 48 Charger was built. Its first flight was from San Diego’s Lindbergh field to nearby North Island Naval Air station. We saw him off, ran to our cars and drove across the Coronado bridge to North Island in time to meet him on landing. Convair’s last remaining test pilot was Johnny Knebel who did most of the testing, then NASA/Ames pilots flew a 10-hour test program followed by a Joint Services Flight Test Program. Pilots from the Air Force, Army, Marines and Navy evaluated the plane and many of them had a hard time controlling the aircraft.

On its 196th flight it was being flown by a Navy pilot performing an evaluation flight when it crashed and burned at Lindbergh Field. The pilot ejected at the last second and landed on top of one of Ryan’s hangars, but no one saw him eject and it was a while before he was found as he was hidden from view due to all the smoke from the burning aircraft. He broke his foot when he ejected when it became entangled under the instrument panel.

North American Aviation got the production contract, not due to the crash but to politics, which is another story. North American’s version was known as the OV-10 Bronco.

Even though three aircraft companies bid on the contract and none knew what the other was designing the three completed aircraft were strikingly similar. This was understandable given the performance parameters spelled out in the RFP. The plane was to have a wingspan of around 20 feet, operate from unimproved roads, the landing gear had to withstand a 20-fps sink rate, have twin booms, turbo-prop engines (the aircraft had counter rotating propellers to negate the effects of torque) and STOL abilities to clear 500 feet over a 50 foot obstacle. This pretty much dictated what the aircraft would look like. All three companies thought the requirement almost impossible to meet but the RFP was not relaxed.—By Richard E. Bruce

The Model 48 Sitting on its Tail at Lindbergh Field, San Diego, Ca. 1966

Building Convair’s COIN Aircraft

Author, in upper right-hand corner, working on the COIN

Model 48 Tie Tack Presented to Workers at Roll Out

I’ve been working on R/C scale models of the Charger; starting with a 1/24th scale indoor electric model. That flew so well that I enlarged a second model to 1/8th scale. This also flew well, except for hot landings where you had to pay attention and bring it in under some power. I’m now working on a slightly larger 1/7th scale (the largest that will fit in my SUV) that will feature more scale-like flaps. Interestingly, I found a flight test report where the model demonstrated pretty much the same flight characteristics as the full scale Charger. I wonder if this could be constructed as a homebuilt at around 3/4 or 7/8ths scale? It has a bumblebee cuteness to it!