By Peter B. Mersky

Editor’s note: Peter Mersky has written 16 books on military aviation, including the first book outside Israel on IAF aces. Besides many magazine articles, he has reviewed some 700 books for various publications, as well as his own regular (since 1982) column for Naval Aviation News, the U.S. Navy’s oldest periodical. He is also a retired USN reserve commander as well as a former editor of “Approach,” the Navy’s aviation safety magazine.

Iftach Spector, a retired brigadier general of the Israeli Air Force (IAF), is a bit of a mystic, looking at his life with questioning expectancy: I see it all before me but why and how does it all exist, and why are the people here, now, going through all they experience with me? Is it love, dedication, patriotic fatalism? He wrote “Phantoms Over Israel” (Amazon Digital Services, $3.95 for Kindle) an autobiographical novel, to answer himself, maybe to give his questioning, occasionally troubled life some answers. A soldier deserves those answers.

Lt. Col. Saul Toledano is the commanding officer of the “Hammer” Squadron. They fly the American McDonnell Douglas F-4E Phantom II, one of the iconic jets of the mid-20th century, which, along with another American jet, the McDonnell Douglas A-4E Skyhawk (and subsequent IAF modifications), formed the backbone of the IAF, particularly during the intense three-week war of October 1973. This war is sometimes called the “Yom Kippur War,” because it began on Oct. 6, 1973, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar (in reality, Iftach Spector commanded 107 Squadron during the war.)

The novel, translated into English by Sam Gorvine, covers the first week of the war when it seemed that Israel was being overwhelmed by Egyptian and Syrian forces. The IAF squadrons were losing Phantoms and Skyhawks every day, along with their highly trained flight crews. Squadron messes were decimated and there were empty chairs every night. Vast arrays of Soviet supplied surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), supplemented by radar-direct anti-aircraft guns provided the Arabs with seemingly impenetrable killing fields that batted the hapless Israeli aircraft from the skies.

It is this bloody time that Gen. Spector describes with such heartfelt anguish and accuracy. After all, he lived it and his writing is among the best I have ever seen. Saul Toledano is a heart-breaking mix of courage and personal doubt. He wants his squadron to succeed, to defend its embattled country, but his intense emotion and anger at what he perceives as meddling and indecision from his superiors combine to immobilize his ability to fight the war as he knows he should. He has the aircraft and more importantly, he knows he has the dedicated, skilled airmen to do it, but the colonels and generals above him, many of whom he has known throughout his career, appear oblivious to his concerns and that lack of understanding make his job that much more impossible to accomplish.

Added to this frustration is concern for his stricken mother, in her own right a long-time fighter in the early days of Israel’s struggle to become a nation amongst a warren of Arabs bent on its destruction. We only see her once in the book, but she helps define her son’s heritage and his personality.

After an introductory poem that touches on the death of his father during a raid against Nazi positions in the Middle East, the book opens with a post-mission “belagan,” Hebrew slang that translates roughly into a “big mess.” Disorganized orders have thrown Toledano’s squadron into disarray, and he has to wade through it all to stabilize his men. It is here that we first encounter the terror of the SAMs, “unmanned killer pipes” as the author calls them. New orders demand another strike against the “eternal dreaded foe” in the northern theater – Syria. The toll in the first days of the 1973 war had been terrible. Even with U.S.-supplied electronic countermeasure (ECM) pods, the Russian missiles had taken out a terrible number of IAF aircraft and crewmen.

Then, it’s a frantic scramble to launch on the new mission. Toledano is now just another combat leader as he rips open the sealed orders with their specialized charts and photos as his desperate squadron gets ready to taxi out from their underground hangars.

Spector’s description of action is strong and colorful. “[Saul] raises his eyes from the map for a moment and looks out of Toledano’s rear seat. He sees an unusual sight: the entire Air Force rushing north. Veritable armadas of fighter planes are streaming over the Jordan valley. Additional formations come pouring out of the mountains like black drops, joining the stream. The entire Valley sky is striped with the distinctive black smoke trails of the Phantoms.” The phrasing is crisp and sharp. “Shuli orders a right turn and their three Hammers leave the main stream and head due east, toward a bypass. They cross the Syrian border immediately, and their ‘Ascot’ formation now drops lower and assumes an arrow shape. In his Number Three’s cockpit, Mossik pushes aside a small trash pile of maps and photographs, now useless, and sticks close to the leader.”

You’re in a low-level gang fight preparing to go into a knife-to-knife duel over the desert, the ancient land of the Bible. No such description has even been portrayed in modern literature. You feel like you are in one of the two cockpits as your Phantom rockets over the Syrian hills to take out a dangerous missile battery that is already locked onto your fighter.

Later, when a colossal drop on intelligence data threatens his squadron’s operational safety, Toledano must control his outrage and launch another mission against unknown Egyptian bridges being thrown across the Suez Canal. Pre-mission reconnaissance photos are inadequate; the bridges are too small, too “thin” to show up in the black-and-white images. Only his skill and sharp eyes can find the spans that will convey the Egyptian army across the embattled waterway.

“Phantoms Over Israel” is written in the present tense as the characters as well as the author think, speak and act. It’s a difficult mode in which to write. We don’t talk like it in normal speech and it is easy to get confused in a lengthy narrative. The burden of command, especially in heavy combat, is one of the main themes and Spector writes with an authority gained only through his own hard, unforgiving experience. The Yom Kippur War was nearly the end of Israel. The IAF was fighting for its own life as well as for its country. The Arabs had never come so close to destroying their hated little neighbor.

Occasionally the reader is stopped, brought up short, along with the CO, as he realizes a truth that he hadn’t considered before: the uncertainty, the surprise of all-out war, where men die, machines drop from the sky wrapped in orange flame, no matter how well-planned the mission. Be prepared for uncertainty is all he can now tell his men as they brief for yet another strike.

Those of us who grew up on stories of air combat will not be prepared for how Spector writes. This story is not for children looking for dogfights with twisting and turning fighters spouting flame from the guns and heroic adversaries dueling in an azure sky. It is down and dirty and men are dying on both sides even as their friends and commanders deal with more missions. We will be surprised, perhaps shocked at how the author drops his depiction of characters. The closest comparison is “The Hunters,” James Salter’s 1958 tragically wonderful novel about the Korean War. Indeed, Spector’s final paragraphs are just as chilling and insightful as those in Salter’s account of combat between the North American F-86 Sabre and the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15. Both should not be missed.

“The sky above is still dark and the stars large; the air is cold and smells of damp concrete and sand. The truck backs up and drives off. As it passes, its lights illuminate the heavy concrete walls, the faces of the mechanics and the great hulls of the fully armed Hammers…” Even the startup becomes a poem from only someone who has done it countless times and can write about the procedure with the ease of an artist. Spector uses different color as easily as an artist employs his palette to describe the different skies of the Middle East, or the stabbing fingers of flame thrusting behind F-4s taking off in afterburner in the still-dark of pre-dawn. Some authors struggle to create these word pictures. Not Spector.

Names from the Bible – Moab, Red Sea – are the everyday scenery these modern chariot-drivers soar over on their way to engage their long-time enemies, also from the Bible.

One by one, as the terrible days progress, the squadron and Saul Toledano lose men and friends, the big, hulking Phantoms fall. Sometimes their crews survive, but too often they don’t. It’s war in the Middle East, like no other battlefield in the world. It’s the heart of the book, fighting the enemy, fighting themselves, struggling to hold onto life and their worlds of family and country. Could the Arabs ever have known how hard it all was? All for a few thousand square miles of contested but loved ancient earth.

Then, on a vital mission into the heart of Syria, Toledano’s courage fails and in the heat of battle, he turns his Phantoms away from the target. He has to report the drastic retreat, opening himself up to everything imaginable. Will he be branded a coward, will he lose command of his squadron? The agony and suspicion of the aftermath opens rare windows into the life of a squadron commander and the question of mid-level leadership in combat that is seldom seen. Saul spends endless hours tormenting himself, second-guessing his decision to abort the mission to Damascus, trying to believe he is not a coward, but a squadron commander with definite and important responsibilities.

This is not a book we read as wide-eyed kids, full of air-to-air combat, yet that story is there. But it is more of an adult story, reinforcing the knowledge that such combat was a small, albeit important aspect of the life of a squadron in war. The contest with his terminally ill mother, mortal enemies who love each other as only a mother and son can, enduring all of life’s terrible hardships living only to fight each other when needed, is an unexpected but illuminating sideshow that leaves both the reader and Toledano drained at the last moment he will see her when he realizes she will be leaving him soon.

Then, the terrible mission, delayed, delayed again, as the exhausted squadron waits, prepares, and waits again. The launch into the choking heat and haze of the Middle East, every crewman alone in his cockpit, 12 aircraft, 24 anxious young aviators flying toward the SAMs and MiGs, watching a third of their group go down with eight of their friends somewhere in the sea or sand, also terminally alone. Spector’s terrible, burning prose goes on, painting the experience with awful accuracy. He has been there many times.

The final paragraphs are romantic and chilling, an example of fine, dramatic writing, almost Hemingway-esque in “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” “Phantoms Over Israel” is a bit heavier in style and theme by an Israeli author, highly experienced in his military craft, who has written what might be considered one of the best novels of the air war. Is Hollywood listening?

To purchase, click here.

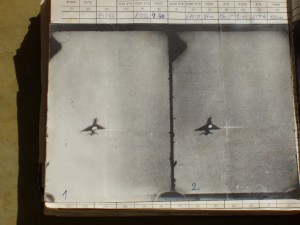

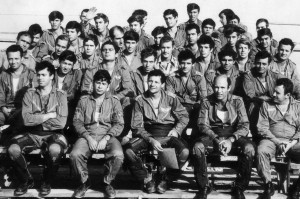

Retired IAF Brig. Gen. Iftach Spector had an incredible career; in the lead photo, he is shown returning from a mission aboard an IAF Phantom or “Kurnass.” He also flew Dassault Mirage IIIs while in No. 101 Squadron (top left) as well as General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcons (top right); among his logbook treasures are these gun camera shots of a Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 kill (middle left). Both officers and ground crewmen took pride in the 107th’s F-4s, as shown in this image (middle right); this 107 group shot obviously came at the end of a busy day (bottom)! Photos via the author.